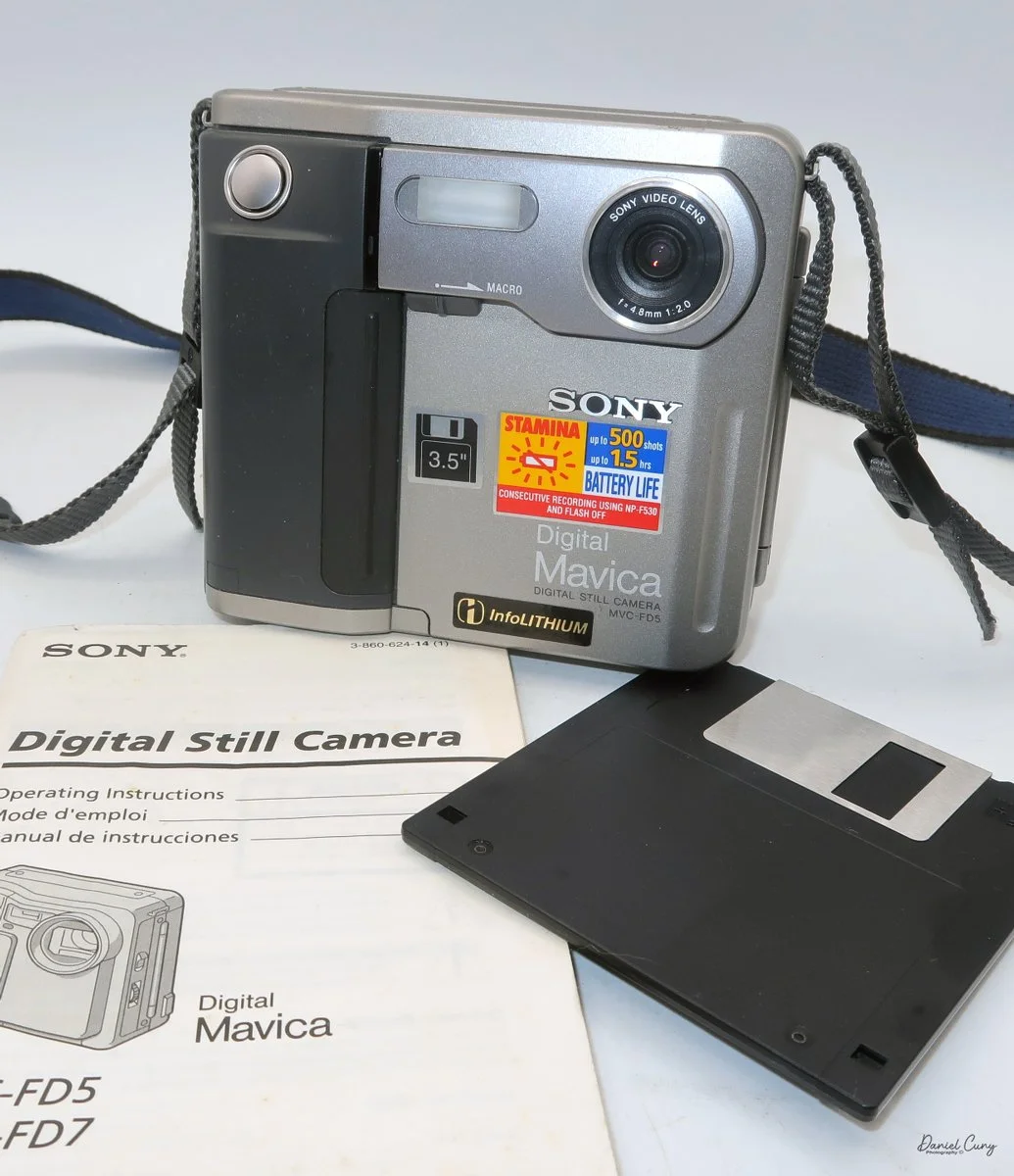

My Sony Maniac MVC-FD5 camera.

I started working in a retail camera shop way back in 1975. The store where I worked was dominated by non-professional photographers, with more of a consumer-based customer base. We sold a lot of film and processed a lot of film. At that time, the store where I worked had a good mix of simple cameras, such as the Kodak Instamatic, and some of the more basic Polaroid models of pack cameras.

But if you wandered over to the more professional side of the store, the cameras on that side of the store had Nikon F and Nikkormat, Minolta SRT series, Canon FTb, Pentax Spotmatic, mainly single-lens reflex and simpler rangefinder cameras were available. The market in our store didn't offer higher-end brands such as Leica, Hasselblad, or large-format brands like Sinar or Toyo.

My camera with floppy disk, and manual

The owner of the camera shop was always looking at new technology and ways to set us apart from the other local camera stores. I still remember back in 1988, when we were introduced to "new technology" that didn't capture images on film. Still, it was a rather small 2" floppy disk. The odd thing about this new revolutionary camera was that it didn't come from a "regular" camera company, but from the major consumer electronics firm from Japan, Sony. At that time, Sony was known to most Americans for their radios, televisions, and other electronics.

The camera was named the Mavica (magnetic video camera) MVC-C1 which was a consumer based camera which was flat shaped, that fit well in your hand, and held a 2" floppy disk called the Mavipak. At the time, these were what we consider "digital images", but rather Still Video Images recorded onto the floppy disk, and intended to be played back on your television. You could record up to fifty images on the Mavipak. Once the images were taken, you'd connect the camera to your television using the MAP-T1 adapter and display the images on the television screen.

In December 1988, Canon introduced a similar camera, the XapShop. It too was a similar-shaped camera that captured still video images on a 2" floppy disk. While both cameras were making a splash in the market, it wasn't until early 1989 that the Sony MVC-C1 became readily available to consumers.

At the time, the idea of capturing images on a floppy disk was odd, and the image quality was poor. Also, when the camera was introduced, it had a hefty price of $650.00 for the Sony and a similar price for the Canon XapShot kit, which, for our consumer-based market, was a steep purchase.

Still, the owner of the camera stores thought well enough of the cameras that we picked up a few of both the Sony and Canon lines of still video cameras, and for a while, we did well selling them to the early adopters in the community. These were the same people who had early Motorola mobile phones.

Sony Digital History:

Sony's ascent to the top of the digital imaging world didn't happen overnight; it was the result of decades of transition from analog video heritage to high-resolution silicon. While many associate the "digital revolution" with the late 90s, Sony's groundwork began much earlier with a device that wasn't technically digital, but fundamentally changed how we perceived photography.

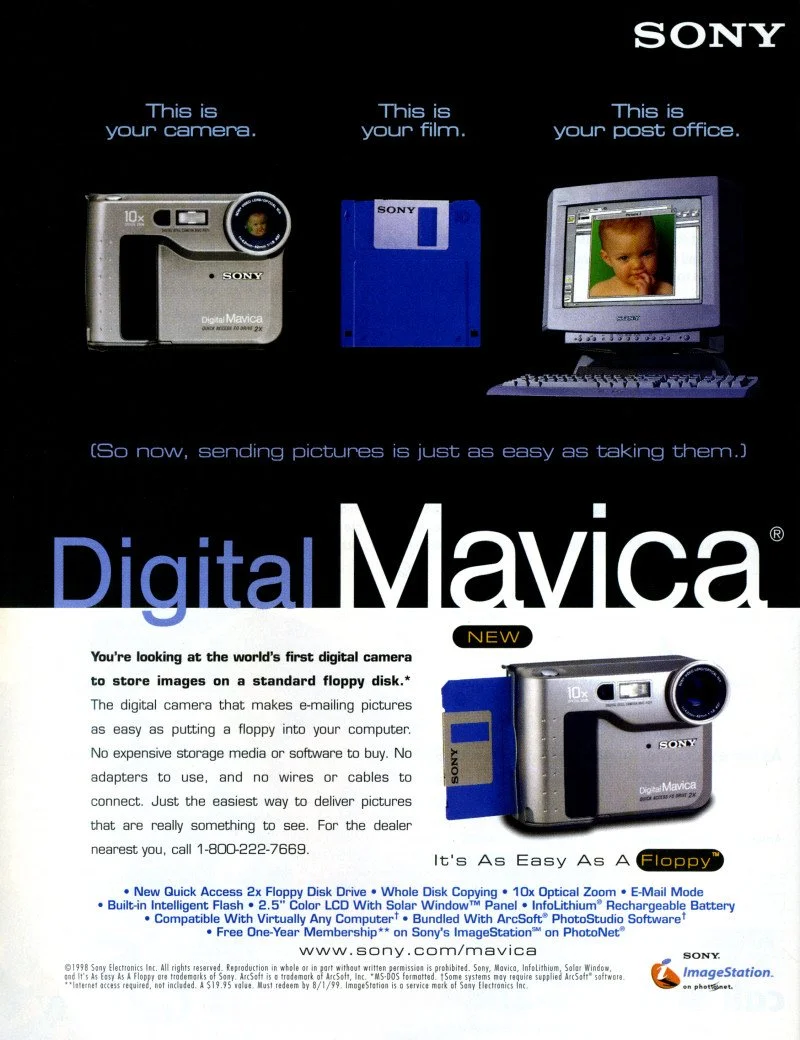

Sony Mavica advertisement.

In 1981, Sony unveiled the Mavica (Magnetic Video Camera). It is often cited as the spark for the digital revolution, though it was actually a "still video" camera. Instead of film, it recorded analog signals onto a proprietary 2-inch floppy disk called the "Mavipak." While the resolution was equivalent to just 0.28 megapixels and intended for television viewing, it proved that the industry could move away from chemical processing toward instant gratification.

It wasn't until the late 1980s and early 1990s that Sony moved into fully digital territory. In 1988, they introduced the MVC-C1, the first Mavica aimed at consumers. However, the real breakthrough for the masses arrived in 1996 with the Cyber-shot DSC-F1. This camera featured a distinctive swiveling lens, a built-in flash, and a 1.8-inch color LCD screen—a luxury at the time. It utilized a 0.35-megapixel CCD sensor and marked the birth of the "Cyber-shot" brand, which would dominate the point-and-shoot market for the next two decades.

In 1997, Sony released the Digital Mavica MVC-FD5 and FD7. These were iconic because they used standard 3.5-inch floppy disks as storage media. While competitors were struggling with expensive, proprietary cables and software, Sony users could pop their disk into any PC and view their photos instantly. This ease of use allowed Sony to capture roughly 40% of the digital camera market by the end of the 1990s.

As the 2000s began, Sony pivoted from a gadget manufacturer to a serious contender in the optics market. By acquiring Konica Minolta's camera business in 2006, Sony gained the mechanical "know-how" of traditional SLR systems. This led to the birth of the Alpha series.

From the experimental Mavica to the launch of the first full-frame mirrorless systems, Sony's beginning was defined by a willingness to abandon tradition in favor of electronic innovation. They didn't just join the camera industry; they forced it to go digital.

My Camera:

My Sony Mavica MVC-FD5 was introduced in late 1997 or early 1998. It's a fairly large camera, measuring 5" wide by 4.25" tall by 2" deep, and it weighs 1 pound, 5.7 ounces with the battery, strap, and a 3.5" floppy disk installed. The camera has a 4.8mm F/2.0 lens, equivalent to a 47mm lens on a 35mm camera. The camera is a fixed focus camera and in normal mode will focus to approximately 4' from the lens. The camera does have a macro lens. Under the flash, there is a sliding bar you slide to put the camera in macro mode; then the focus distance is 3"-9" from the lens surface.

The images are recorded onto a standard 3.5" floppy disk (1.44mb) which is inserted into the camera through a door on the left side of the camera. On the back of the camera, in the lower left corner is a switch which says, "open". Sliding the button down, opens the door where you insert the 3.5" floppy disk. To remove the disk, press the button inside the disk's door, and the floppy will be ejected.

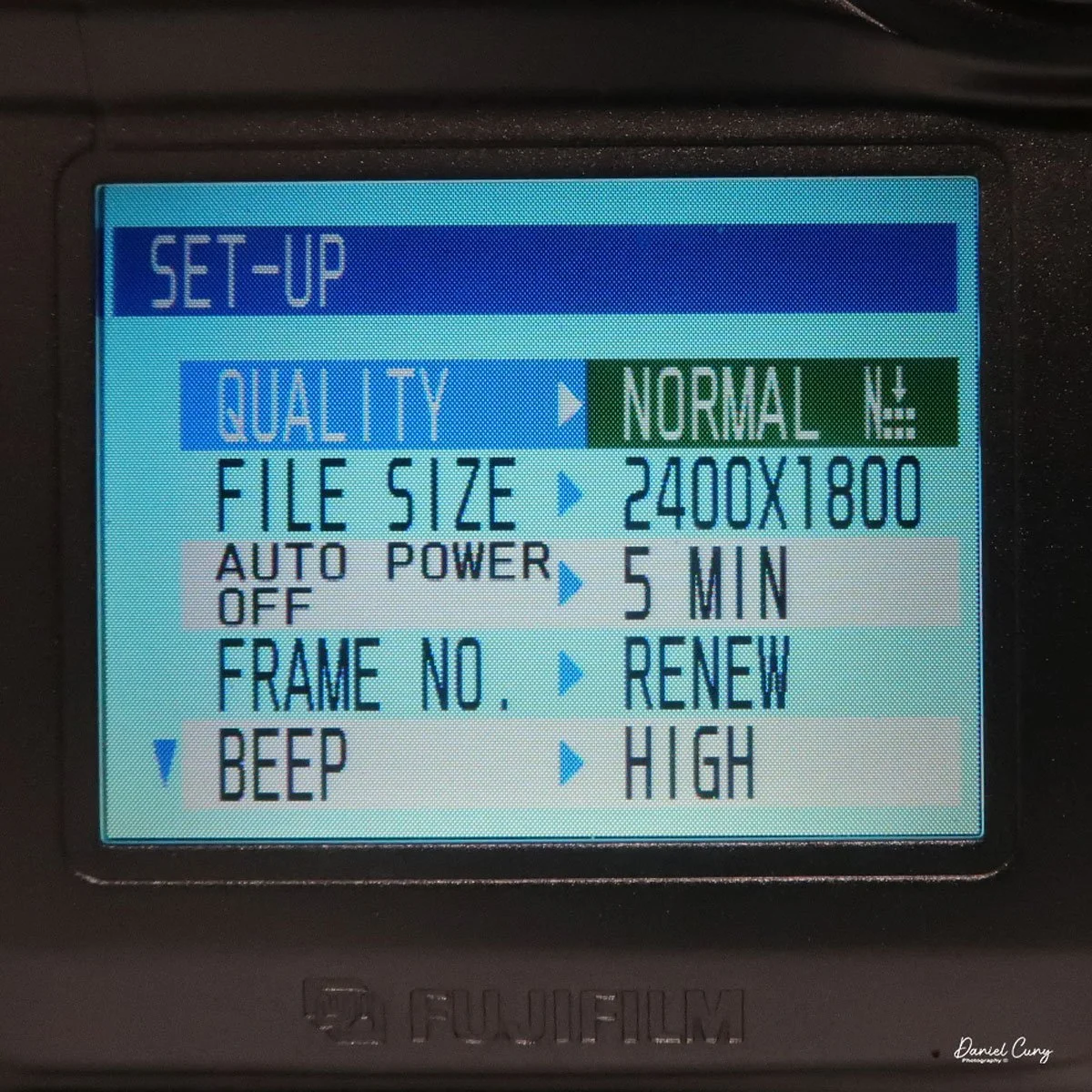

The camera records images at 640 x 480 resolution in JPEG format and has two shooting modes: Standard and Fine. Each floppy disk will hold 30-40 standard images or 15-20 fine images.

All the controls on the Sony Mavica MVC-FD5 camera are located on the back. The controls are around the main 2.5" screen, which has a total of 61380 dots. Once the camera is turned on, which is done by a sliding switch to the right of the screen, named "power on/off". Slide the switch down to turn the camera on, and to shut it off, slide it down again.

It's very interesting, and something I didn't remember from owning this camera soon after it came out in the late 1990s. Still, once you turn the camera "on, and there's a floppy disk in the camera, you'll hear a noise of the internal disk drive spinning and making sounds because the camera is checking the disk, making sure it's seated correctly and can write to it. It's also the sound you hear when you switch the button on the back of the camera from "play" to "camera," or vice versa, as the camera spins the disk to read images or prepare to accept them. It also makes a sound when in "play" mode, as you go from one image to another. Here's a short video of turning on the camera and taking a photo.

Video showing the camera being powered on and the time to record an image with camera sounds.

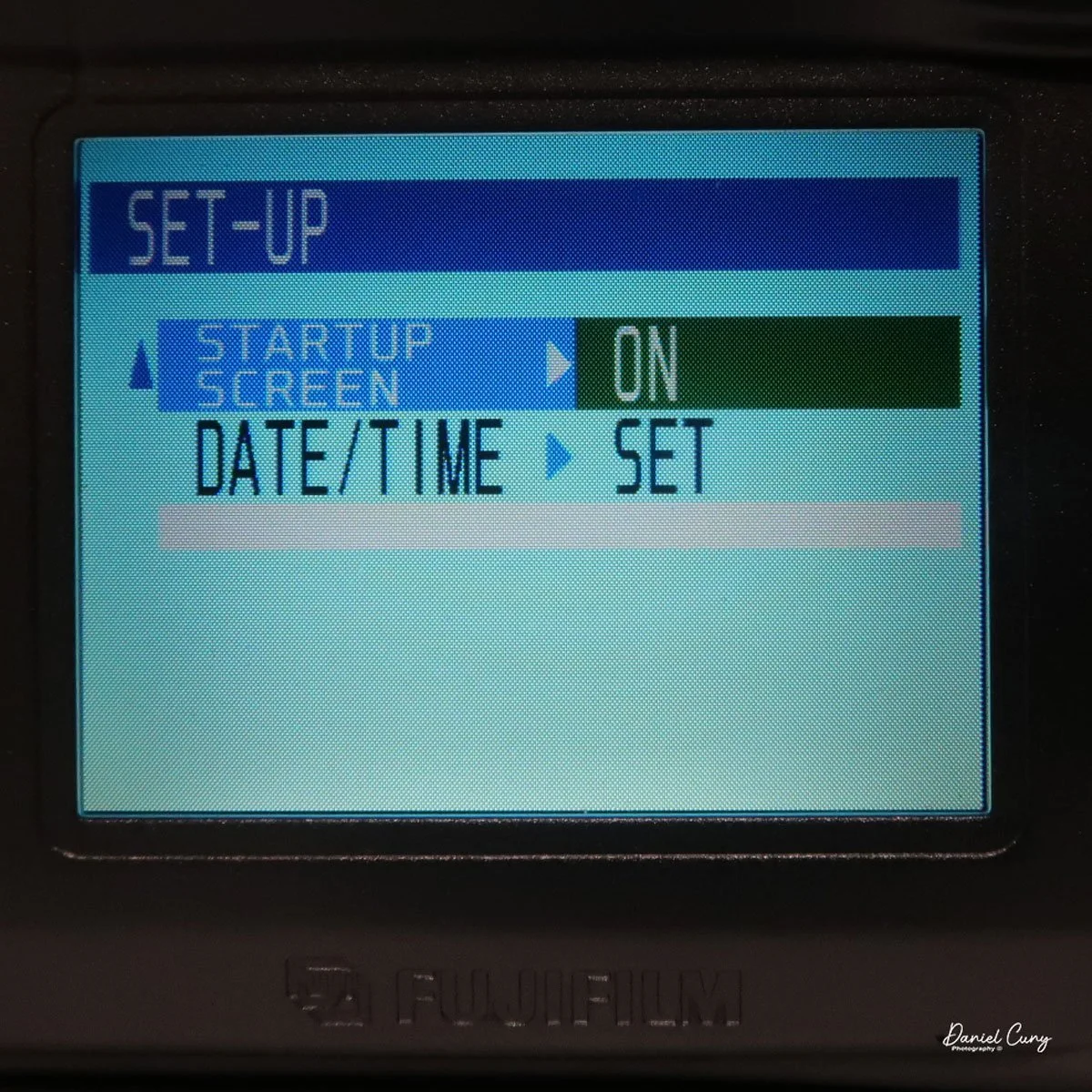

Once the camera is powered "on", most controls are set via a rocker switch and a button to the lower right of the camera's screen. As mentioned previously, there is also a switch for "camera" or "play" which allows the camera's settings to be set in each mode. If you press the rocker switch when it's in the "camera" mode, a menu will pop up with options for Clock Set, Beep, Field/Frame, Quality, and Return.

In the "play" mode, the menu settings are Clock Set, Beep, Format Disk, Delete, Protect, and Return. Interestingly, Clock Set and Beep are in both the camera and play menu.

One other button on the back of the camera is "display," which turns the menu on or off on the camera or in play settings. It lets you focus on the images on the screen without being distracted by menu settings that can cover parts of the screen.

Once the clock settings are set, you've turned on/off the beep sound, and you have the floppy disk in the camera. You're ready to power on the camera to take a photo. When you turn on the camera, you'll hear disk noises, see the date pop up on the back, and, in the upper right corner, see a spinning circle indicating the disk is turning inside the camera. Now you're ready to take photos.

The camera doesn't have a viewfinder, so once the camera is powered on, and the screen has gotten past the time function, you've seen the spinning disk, the camera will go into "live" mode, where you'll see the images you're pointing the camera at on the back screen. Like many cameras from this era, the screen is dark, and you can barely see an image on a bright, sunny day. You can brighten or darken the screen with two switches to the left of the screen, named "bright" with a "+" on the top button, and a "-" on the bottom.

There is no shutter or aperture control on the camera, as exposure is automatically controlled. You can make the images brighter or darker by up to 1.5 stops by changing the EV setting on the camera's screen once the camera is turned on and in "camera" mode.

Another oddity of this camera, as with more modern cameras, is that the Sony Mavica MVC FD5 doesn't display the "just taken" photo on the screen once it's captured. To see that image, you'll need to switch from "camera" to "play" mode. The camera will whizz the floppy disk, and you can preview the previously taken image. In the "play" mode, you can view either single images by pressing the arrows forward to backwards, or you can press "index" so you can display a series of six images at a time and scroll to the image you want to see, and press the rocker button to display. PLEASE REMEMBER: every time you switch from one image to the other, the camera displays a message on the back screen that says "accessing file," and it takes a few seconds to show the image.

In the "play" menu, you can also "protect" or "delete" images. Still, like the other settings, it takes a few seconds for the camera to complete the request, since it's basically a small computer with a built-in floppy disk and has to find, access, and complete the request you're making.

At the bottom of the camera is the door, which you open and insert the charged battery to power the camera. The camera's battery isn't rated in shots, but in time. Once you power the camera "on", in the lower right-hand corner of the screen, you see the time in minutes remaining on the battery before recharging is needed.

My Images:

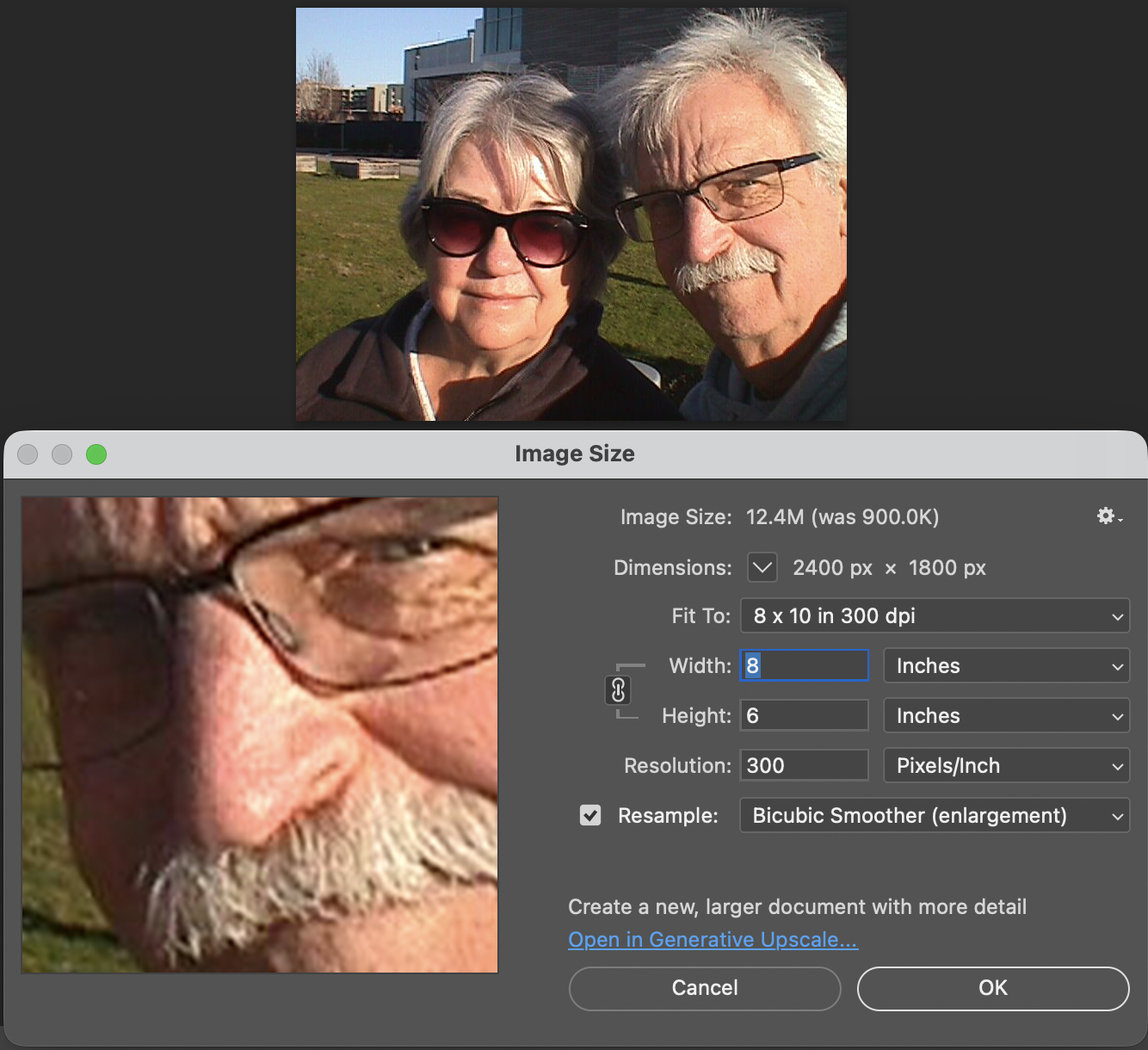

My wife, daughter, daughter's dog, Bean, and I went for a walk on the town's downtown walkway on the Columbia River. It's a relatively new section of town with shops, restaurants, and housing. It was a sunny and somewhat warm January day in the Portland, OR area, so I took the camera on our trip.

Since it was a bright sunny day, the rear screen was difficult to see, especially when you're trying to have the sun on the subject, meaning the sun is also hitting the screen as you're taking the images.

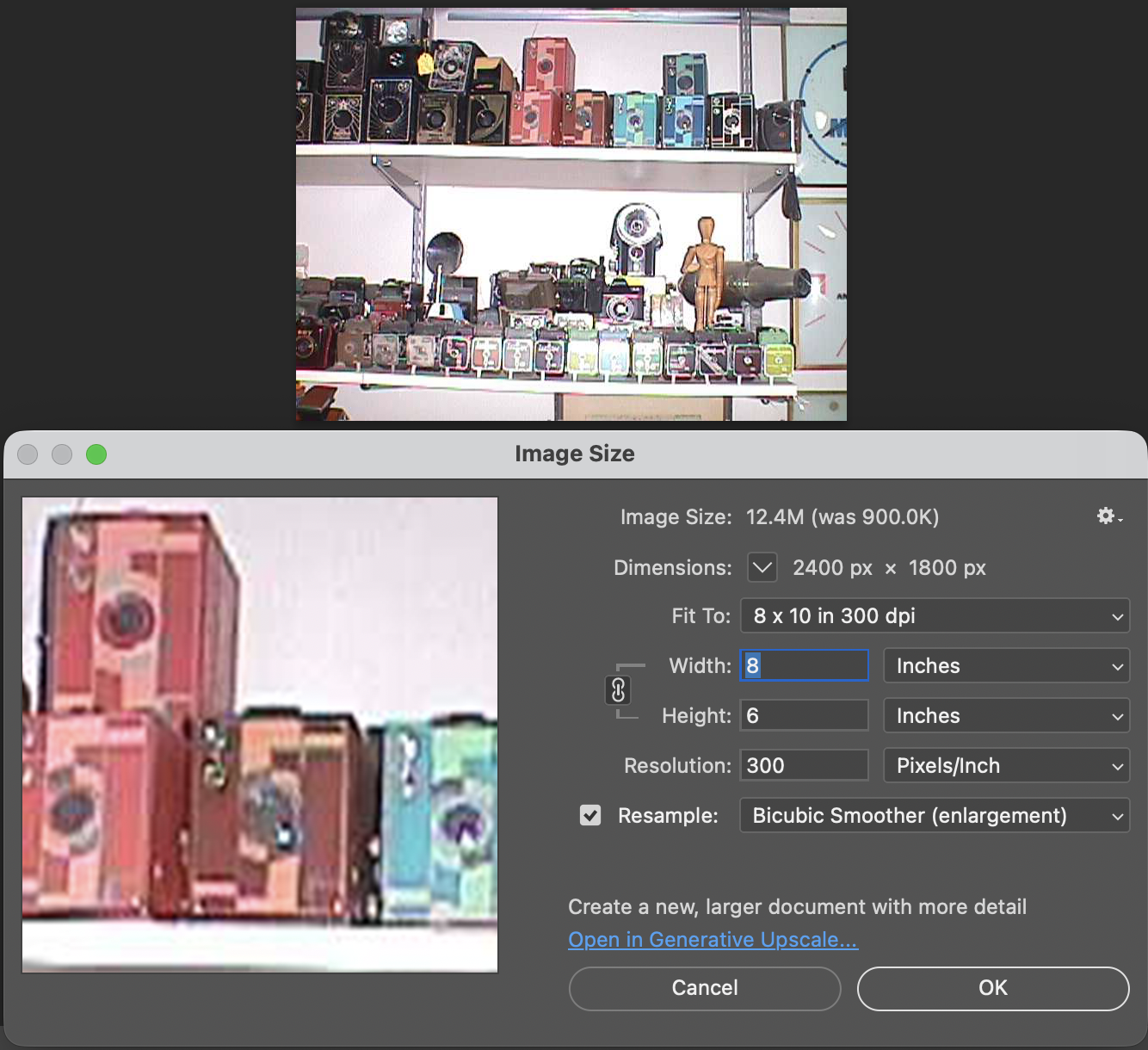

Another interesting fact is that these files are small. Even the largest files the camera produced were only 70kb for Fine and 34kb for Standard images. These were specifically made for viewing on your computer or television, and are not really intended to be printed, especially not anything larger than the standard 3x5 photo.

Here are some images from our walk.

Conclusion:

I never would have guessed that a 2-inch floppy disk would eventually bring the Nikon F's reign to an end. The MVC-FD5 wasn't a 'pro' tool—it couldn't compete with a Hasselblad for clarity—but it offered something those giants couldn't: the end of the waiting period. It traded resolution for time, a trade-off that eventually redefined the entire industry.

It's interesting for the young photographers of today to compare this camera to what's available on our phones; it's an eye-opening comparison:

Camera: Sony Mavica MVC-FD5 (1997) Modern Smartphone (Approx.)

Resolution: 0.3 Megapixels (640 x 480) 12 - 48 Megapixels

Storage Media: 3.5" Floppy Disk (1.44 MB) Internal Flash (128 GB+)

Photo Capacity: ~20 "Fine" Image 30,000+ Images

Write Speed: ~4-6 Seconds per photo Instant

I had owned this camera sometime in the late 1990s. It wasn't long after it was introduced that I purchased a used one. It was in 1999 when I had one.

Thinking back, this was a pretty fun camera to shoot with, and now that I have it again, it's fun to hear it make the different noises as it accesses the files to show on the screen. The images are very small and, as mentioned, made for screen viewing, not much resolution to make prints from. Even by today's computer standards, the images look very pixilated due to the higher resolution of today's screens.

I'm happy to have this camera back in my collection, more as a marker of digital photography's growth than something I'm going to use daily. It is, just like with older film cameras, fun to see how these image-making machines have progressed over time.

Thank you for taking the time to read a bit about this older digital camera from my collection. Next week will be the final installment of January's Early Digital month, and I have a rare and good one for you. Please remember to keep an eye out for it.

Here are some of my other Camera Reviews.

I also have a store on eBay, Cuny's Cameras and Photo, where I sell some of the cameras reviewed, along with many other camera odds and ends. If there's something that interests you, drop me a line, and I'll offer a discount.

Until next week, please be safe,